DID YOU see Kung Fu Panda 2 and wonder why the best animation we can manage is an unintended horror show in 3D called Bal Ganesh? How is it that in a cultural legacy so vibrant with children’s tales, the only stories we have to tell through animation involve rigid gods without a sense of fun?

Indian animation, which at the start of this decade was predicted to be the next big thing, is facing a crisis. But just as the hype begins to turn sour for Indian animators, comes an interesting experiment in the form of an irascible monkey and a worldly parrot with a penchant for scotch whisky.

To read media reporting on the Indian animation industry is to be buoyed with a sense of rainbow-hued goodtidings, much like the sunny commentary surrounding the country’s GDP. It is reported, for example, that by 2012, the industry is headed for a turnover of $1 billion, comprising a 1 percent share in the global animation industry. Much of it to give way to a home-grown army of animators exercising their (now) matured talent on Indian characters, telling Indian stories to Indian children in an Indian way. The trouble with that narrative is that it’s a decade old and hasn’t come true. Animation is an intense mix of high creativity and hard labour. Behind every frame and every detail is an army of specialists who model, structure, colour, texture, animate, design, imagine and dialogue the characters and the world they inhabit, literally, over years. Given the sheer quantum of labour, it’s no accident that this industry was among the first to open itself to outsourcing.

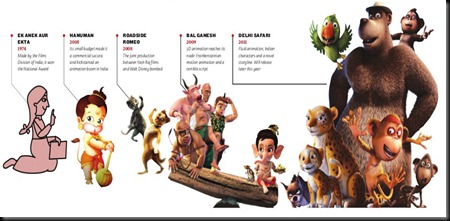

The expected evolution from outsourced labour work for, say, a Walt Disney feature, to the making of a homegrown story, indigenously imagined and told, has not happened.

Neha Shah Pastakhia, 32, has been in the animation industry since 2002. She says, “It’s a factory floor in India with a supervisor foreman who demands how many seconds of finished labour I am going to give him today. There is zero creativity. Forget about original work. Anyone who has tried it has closed down. There is a saturation point to doing someone else’s work and I know many in the field who have been working for more than 10 years and are just waiting to get out.”

The ire lies in the paradoxical nature of the work. Animation, as opposed to other kinds of outsourcing, is an aesthetic art and even in its drudgery requires craft and skill — in fact, the ownership and investment in the creative aspects often fuels the drive to work on all the less creative, but equally important laborious details. So to understand Pastakhia’s position, imagine you are trained as a painter and see yourself in the same profession as Pablo Picasso, but then find that the only job you are allowed to do is to fill in colours on numbered squares belonging to someone else.

Bollywood doesn’t see business sense in animation. The most it does is halve the duration, slash budgets, discount quality and make it mythological

What’s worse is that even the coloured squares are now diminishing. In the aftermath of the economic crisis, animation outsourcing business is not what it once was. The projects have become fewer, the market has become aggressive and India is far behind its competitors.

RAM MOHAN, chairman of Graphite Multimedia and an industry veteran of 54 years, says, “Even in the outsourcing market, we are nowhere close to the competition. Korea and Singapore produce 10-15 seconds of work per day per artist. China produces 13 seconds. The average Indian animator’s output on a high quality work is 0.5 seconds per day.”

This ineptitude is in large part due to training. Says Mohan, “It’s a mercenary approach. Take money and hand out a certificate. Often the guy who’s passed out the year before is your teacher this year. Young people are misguided by the hype surrounding animation. They have been given the impression that all you need is a 6-8 month course in software.”

The training racket churns out an average of above 10,000 animators each year. On an average, the institutes charge up to Rs 3 lakh. In a market environment, where the lowest bids that get an outsourcing project are getting lower still, salaries have fallen (the starting salary of an animator today is around Rs 7,000 as opposed to Rs 11,000 in the early 2000s). Meanwhile, the mid-level animators are losing their jobs to newly minted ones because they will work for less. The result is a stasis four to five years after committing to the profession, living on contracts with no guarantee that others will follow.

Sekhar Mukherjee, head of animation, National Institute of Design, summarises, “The picture is grim. This is a turbulent time for the industry. The hope was for a contentheavy culture. We are once again seeing mythological releases. There is very little original work.”

The way forward for the Indian animation industry is to graduate from a labour camp to original creations. That seems difficult today because Bollywood refuses to see the business sense in backing an animation film that will take three years in the making, cost money, require talent and then fizzle at the box office. The most it’s willing to do is halve the time taken, quarter the budget, discount quality and make it mythological under an ‘also educational’ logic.

Hence the buzz around India’s first indigenously made stereoscopic (you will need glasses) 3D animation feature — Delhi Safari. Slated to be released in India soon, Delhi Safari begins at Mumbai’s Borivili National Park, where a special day turns tragic when human encroachment leads to the death of Sultan — the leader of the leopards. Bajrangi, the militant monkey, is keen on waging war on the humans, but Bagga — a bear who is a pacifist and Bajrangi’s anger management therapist, prevails on the animals to give diplomacy a try. With the aid of the talking parrot Alex — a south Mumbai hedonist — the animals begin their adventure from Mumbai to Delhi, to meet the leader of the humans who sits in a place called Parliament. Made by a small Pune-based animation studio called Krayon Pictures, the film is directed by Nikhil Advani and was four years in the making. Its cost, as a source reveals, is Rs 27 crore. The dubbed English version that’s been made for international release has songs by Vanessa Williams and features Seinfeld’s Jason Alexander.

Given the future facing Indian animation, it would be interesting to see how Delhi Safari, with its original characters and novel script, fares at the box office. Indian animation needs the animals to do well.

No comments:

Post a Comment